This election cycle, TCU is presenting a series of events titled Elections, Democracy

and Social Values. The series aims to explore various viewpoints and aspects of an

election and engage TCU’s diverse community in voting as informed, responsible citizens.

This election cycle, TCU is presenting a series of events titled Elections, Democracy

and Social Values. The series aims to explore various viewpoints and aspects of an

election and engage TCU’s diverse community in voting as informed, responsible citizens.

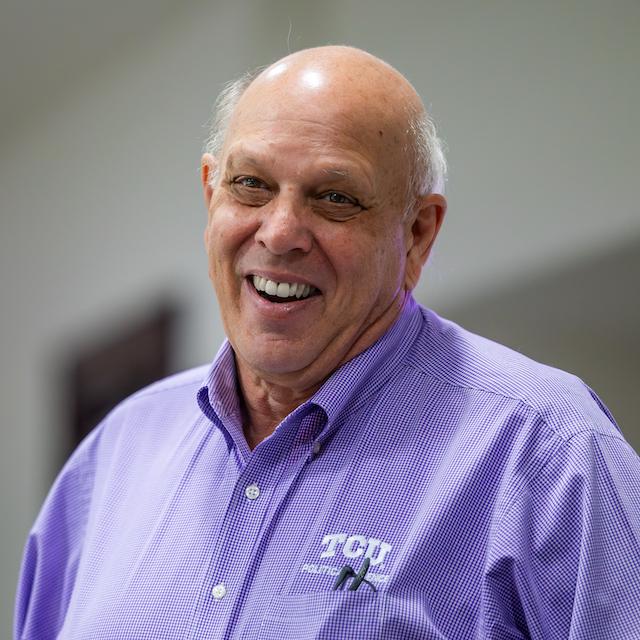

The third event in the series, “Between ‘Not Perfect’ and ‘Excellent’: Evaluating American Elections with Jim Riddlesperger” will feature the professor of political science as he delves into decisions that have made fair elections difficult. Ahead of the event, Riddlesperger answered a few questions on the topic at hand for TCU News.

The title of the event says that our elections are somewhere between “not perfect”

and “excellent.” Can you expand on this idea?

We all know the difficulties associated with presidential elections. Just to name

three: (1) The Electoral College makes it where only the votes in seven swing states

will determine the outcome of the election, rendering voters in 43 states feeling

like their vote is discounted. And, of course, there is always the possibility that

the candidate who wins the popular vote can lose in the Electoral College. (2) Republicans,

of course, think that there are states in the country with policies that allow people

to vote who are not properly registered. Though the evidence for this is not strong,

a huge number of voters think this is a problem. (3) Democrats believe that the Republicans

are intentionally excluding eligible voters from participating with restrictive voting

laws, and that this alleged suppression might affect the outcome of the election. So,

in a nation that prides itself on free and fair (excellent) elections, we have issues

that render the system “not perfect.”

What changes in the political system over the years have contributed to what we’re

seeing now?

What changes in the political system over the years have contributed to what we’re

seeing now?

There are many, many changes in the election system over time. This is very difficult

to summarize because each of the 50 states can change its primary and general election

rules for each election. There are literally dozens of changes in the law each election:

building and maintaining election rolls, the logistics of elections, identification

necessary to vote, the machines used to collect and count votes and even how electoral

votes will be cast (see the pressure last week for Nebraska to change how it was to

cast electoral votes as an example). This is a complex and ongoing issue. The key

here, in my opinion, is that under the United States Constitution, states make decisions

about how to conduct elections. With Washington included, that means there are literally

51 sets of rules used across the country.

What pending evolutions do you see today that you think have the potential to change

elections years from now when we look back?

I really fear that this year, if the election is close, there will be huge segments

of voters who might not accept the outcome of the election. That is the evolution

that is most profound. We had contested elections in 1800, 1824, 1876 and 1888, so

this is not an entirely new issue, but with two elections in this century where the

popular vote went for Democrats and the Electoral College for Republicans (2000 and

2016), Democrats feel the system itself is stacked against them, and with former President

Donald Trump not having accepted the outcome of the 2020 election, the potential for

disruption after the election is large. That could be a warning sign for the peaceful

transition of power that characterized our nation through nearly all of its history.

What is the best thing we can do as citizens and voters?

VOTE. And be engaged as citizens. That is the guardrail of democracy.

Between “Not Perfect” and “Excellent”: Evaluating American Elections with Jim Riddlesperger will be held Oct. 15.

For more on Elections, Democracy and Social Values, read Betting on Democracy: Grant Ferguson Discusses Political Predictive Markets and Information, Misinformation and Disinformation: Kristie Bunton on Elections, AI.